The rise of “soft” treatment methods in health care, such as hypnosis, shows a striking parallel to poet Henriette Roland Holst’s statement, “The gentle forces will surely win.” This approach increasingly emphasizes noninvasive techniques, which help with pain management, behavior modification and treatment of mental illness. This article explores the emergence and recognition of hypnosis as a valuable tool in health care, where it is a mild alternative to conventional treatments. While not a panacea, the gentle power of hypnosis is proving to be a valuable complement to traditional treatments.

The gentle forces will surely win in the end – this I hear as an intimate whisper within me: if it were silent all light would dim all warmth would stiffen within. The powers that still encircle love it will, gradually advancing, overcome, then the great bliss can begin that w’if our hearts listen attentively in all tenderness murmurs hear as in little shells the great sea. Love is the meaning of ‘t life of the planets, and mense’ and animals’.

There is nothing that can disturb ‘t rise to her.

This is the nautical knowledge: to perfect Love everything rises with it. Sunken Borders (1918) “The gentle forces will surely prevail,” is the first line of a poem by Henriette Roland Holst (1869-1952).

It emphasizes the power of gentleness and its healing effects. It expresses how gentleness and stillness are able to calm restlessness and bring hope and peace to our minds.  “The gentle forces will prevail” also means that soft, subtle methods are ultimately more successful than harsh and violent approaches. Therefore, it became a widely quoted statement especially in antimilitarist circles, and from 1957 by the Pacifist Socialist Party. Roland Holst wrote it in 1918. It was just after World War I and at a time when industrialization and technical development meant that there was less and less regard for the individual human being. Even in the medical world but also, for example, in parenting and education, dominant natural scientific ideologies, techniques and methods seemed more important than the individual.

“The gentle forces will prevail” also means that soft, subtle methods are ultimately more successful than harsh and violent approaches. Therefore, it became a widely quoted statement especially in antimilitarist circles, and from 1957 by the Pacifist Socialist Party. Roland Holst wrote it in 1918. It was just after World War I and at a time when industrialization and technical development meant that there was less and less regard for the individual human being. Even in the medical world but also, for example, in parenting and education, dominant natural scientific ideologies, techniques and methods seemed more important than the individual.

The problem of stuttering

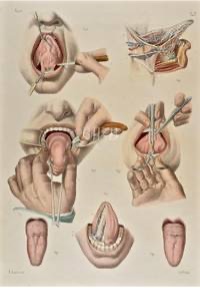

How scientists sometimes handled the feelings and interests of individual patients we see in the experiment with stuttering children that went down in history as the Monster Experiment’. That in the 19th and 20th centuries many people resorted to hypnosis is understandable if you knew what you could face with regular treatment. Patient muteness had not yet been invented, and doctors could initiate treatment at their discretion. Those treatments were diverse and not infrequently experimental. What to do if you fell into the hands of Prussian surgeon J.F. Dieffenbach, who in the 19th century tried to treat stuttering by making an incision in the root of the tongue, with mostly disastrous consequences for the patient.

[1](Bobrick, 2015 Metz, Rik, 2016,) Or what about the idea of creating a school for “speech-impaired children” as proposed by the “Mother of Dutch speech therapy” singing and speaking pedagogue Branco van Dantzig (1870-1942). This school was to provide extra support and help to children with speech impairments, such as stuttering, on the other hand protect children who do not stutter. A recurring idea in those years was that stuttering was not only hereditary but also contagious. And so stuttering children had to be kept away from non-stuttering children.

The ‘Monster Experiment’

As with so many problems in children, there was a theory to prove that parents were to blame for stuttering. American professor Wendell Johnson believed that stuttering did not have physiological or neurological causes and thus could not be found in the stutterer’s body or brain. Stuttering, he said, was learned and caused by the environment. One piece of evidence Johnson saw in the fact that there are significantly more male than female stutterers. After all, men in the Western world bear the yoke of expectation; they are expected to perform more. Whether unconsciously or not, parents transfer this pressure to their offspring and are therefore more likely to see speech problems in the child. That’s what the Dutch speech therapist Mes meant when he wrote in the 1920s: “By correcting or ridiculing, which unfortunately parents and educators today still often consider as a pedagogical measure, the child is first squarely made aware of his mistake, which hitherto he was not aware of. (Knife, 1927).

The Monster Study

In 1939, student Mary Tudor sought evidence for Johnson’s theory with an experiment with 22 orphans from Davonport, Iowa (USA). She wanted to find out to what extent the environment plays a role in the development of stuttering in young children. The children were labeled by the orphanage to indicate whether they stuttered. Of the 22 children, 10 were classified as “stutterers” by their supervisors. The remaining 12 children were fluent speakers. Tudor put together four groups. Groups 1A and 1B each consisted of 5 stutterers. The other 12 children (groups 2A and 2B) did not stutter. Speech was spoken to and practiced individually with each child for about three quarters of an hour. Group 1A, labeled “stutterers” were told by Tudor that they were not stutterers but “normal speakers” who were mistakenly called “stutterers. Group 1B, also five children labeled “stutterer” were introduced to their stuttering. The six children in Group 2A, were not confirmed as “stutterers” but heard that they went through different stages of fluency. Their stutters did have hiccups typical of stuttering. Group 2B consisted of six children of the same age, sex, intelligence and with the same speech rate as the children in group 2A. They were not given a negative label (Tudor, 1939). The children in groups 1A and 2B were told from the beginning that their speech was excellent and were regularly complimented on their pronunciation and fluency. They were also told not to care what others said about their speech. They were allowed to be satisfied with how they spoke. ‘You’ll grow out of it. ‘It’s just a phase, so don’t pay attention to what others say about your speaking skills.’ Things were different in groups 1B and 2A. These children, including stutterers and non-stutterers, received ongoing severe criticism of their speaking skills and pronunciation. They were told that they had a speech problem and that they needed to do something about it as soon as possible. The stutterers in the group were used as negative examples. ‘See him, you don’t want to talk like that, do you?’ ‘The way you’re talking now, that’s how it started with him once. Make sure you don’t start doing that too.’ ‘Never speak unless you are sure you can say it well.’ After six months, three of the four groups showed no substantial changes. In groups 1A and 2B, the “stutterers” continued to stutter and the non-stutterers continued to speak fluently. So the positive approach had worked, according to Tudor, because there were no negative effects. There was also no deterioration or improvement among the stutterers in group 1B. Thus, the negative feedback they had received had no direct effect on their speaking. Among the non-stuttering children in group 2A, a clear negative change in their personality was evident and their speech anxiety took on frightening proportions. Some of them then fled the orphanage. Mary Tudor, who continued to visit the children regularly after the experiment ended, wrote to Wendell Johnson that she thought children would recover, but that the researchers had certainly made a deep impression on the children. Tudor and Johnson concluded that their experiment was successful and clearly proved Johnson’s hypothesis, that stuttering does not start with the child, but with the environment. Those “stutterers” who were approached positively continued to stutter, as did those who received negative feedback. The most significant result was found among non-stutterers who received negative feedback. The children in group 2A showed a sharp decline in self-esteem, self-confidence and increasing speech anxiety. Johnson’s thesis seemed proven: a child does not stutter by himself, but only starts doing so when his environment labels him negatively.

Critique

Johnson and Tudor did not disclose the results favorable to them. It was the 1940s, after all, and reports of experiments conducted on children by the Nazis put the whole approach in a bad light. Only years later did a journalist bring out the investigation report and unleash a storm of criticism as yet. Johnson and Tudor were blamed for misinterpreting their results and especially for not paying enough attention to the impact of their research on children’s mental health. The orphans were chosen simply because they were easier to “use. Neither the facilitators nor the children had been told anything about the purpose of the study. They had even been lied to. In 2007, the judge vindicated the six still living participants in the experiment in their charges that they had been psychologically harmed. The now senior citizens claimed to have had speech anxiety all their lives after the experiment. Together, they were awarded nearly $1 million in damages. (BBC, 2007). The research, titled “An experimental study of the effect of evaluative labeling of speech fluency,” went down in history as the “Sample Experiment. (Rik Mets) The sample experiment is just one example of many in which technique, theory or method are deemed more important than the interests and feelings of patients. We know from history such things as hysterectomy, lobotomy and painful surgeries without anesthesia.

A broader shift

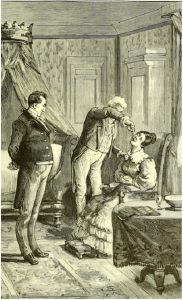

The transition from surgical procedures to more psychologically oriented treatments such as hypnosis is part of a broader shift in the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses in particular. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the medical community began to recognize the limitations and harmful effects of physical interventions for mental illness. At the same time, new psychological theories and treatments began to emerge. One of the pioneers in this field was Sigmund Freud, whose work on psychoanalysis changed the way doctors viewed mental illness. Freud and his colleagues frequently used hypnosis in their treatments. They saw hypnosis as a means of accessing a patient’s unconscious and discovering there hidden traumas and conflicts that were at the root of their symptoms. Thus, the idea that hysteria and other similar disorders stemmed from physical problems in the womb was replaced by the idea that they had a psychological origin. Treatment changed accordingly. Doctors in the Netherlands also suggested hypnotic alternatives. Dr. A.W. van Renterghem did much work on surgical procedures in hypnotic anesthesia. His Hague colleague Arie de Jong writes in his booklet ‘Hypnotism as Medication’ (1888): “…I first applied hypnotic medicine to a stutterer, who had for some time been treated by me with methodical speech exercises and had made relatively little progress. Starting from the principle that in the great majority of cases stuttering is a functional disorder and that it occurs under certain psychological influences, I assumed that the application of hypnotism could certainly bear very good fruit here. I succeeded in bringing the patient into hypnosis very soon, and after convincing myself of his suggestibility, I suggested to him in what I thought to be the most suitable way, whereupon I began to hold speech exercises with him, in which the influence was so evident that the patient spoke almost without stuttering. The patient began to speak more easily from day one. This case was followed by several others, so that I now rejoice in a very interesting material of stutterers, who in public séances, by the great influence of hypnosis on their speech, command everyone’s admiration.”

De Jong emphasizes that it is important to find the most suitable method for each patient and that patience and perseverance are essential in hypnotic therapy: “…More important curative tool, however, is the so-called suggestion, but also only when applied correctly and judiciously. To the uninitiated in the field of hypnotic therapy, suggestion seems so simple that a small child could apply it himself. (*) A young man under my treatment for stuttering was experimented with for 16 consecutive days without any result. On the 17th day, in less than five minutes, he fell into fairly deep hypnosis and I had no difficulty in bringing him into complete somnambulism.” De Jong also points out the importance of the patient’s own input: “Through the so-called autohypnotism, many sufferers have already been treated by me. I have several stutterers perform speech exercises in hypnosis at home. In very sensitive individuals, the suggestion has already been successfully applied in writing several times.”

The gentle forces will surely prevail

Hypnotherapy is a form of therapy that uses hypnosis to bring about changes in a person’s consciousness. It is often used as a gentle, non-invasive approach to address various psychological and emotional problems, such as anxiety, phobias, stress, addictions and pain. In the context of hypnotherapy, H. Roland Holst’s line of poetry can mean that the subtle power of the subconscious, which is tapped during hypnosis, can bring about positive changes. It refers to hypnotherapy’s ability to act on the patient’s psyche in a gentle way, without coercion or aggression, and together with the patient’s personal motivation and desires to achieve improvements. There are numerous examples where hypnosis is used as an alternative rather than with aggressive medical practices. The example of aggressive, even cruel treatment of stutterers is not an isolated incident. Many studies and treatments take on a hypnotic counterpart over time. Some notable examples include:

Surgical procedures

Anaesthesia

The best known is probably pain management. In the 19th century, before anesthesia was widely available, hypnosis was sometimes used as an alternative method for relieving pain and minimizing trauma in surgical procedures. James Esdaile, a Scottish physician working in India, used hypnosis as an anesthetic for patients undergoing major surgery. He successfully performed hundreds of procedures, such as amputations and tumor removals, using hypnotic trance to relieve pain. Later, some chronic pain disorders were treated with surgical treatments, in which nerves were cut or removed. This approach often proved ineffective and often caused more harm. Now people in these cases are turning more to physical therapy, medication and relaxation techniques, including hypnotherapy, for pain management.

Anesthesia in dental procedures:

Anesthesia in dental procedures:

Before the availability of local anesthetics in dentistry, animal magnetism was sometimes used to relieve pain and anxiety. After a period of chemical anesthesia, more and more dentists are using hypnosis to help patients relax.

Overweight

A modern variation of a hypnotherapeutic technique versus invasive surgery is obesity treatment. In a short time, some surgical methods such as gastric bypass became popular. While such procedures are sometimes effective, they are also dangerous and not suitable for everyone. Today, weight loss is also addressed with a virtual hypnosis “gastric band” whether or not combined with exercise, behavior modification and diet.

Pain relief in childbirth

For modern pain management methods such as the epidural, animal magnetism was sometimes used to relieve pain. Pain relief with chemical drugs has been found to have drawbacks, such as decreased awareness that reduces the mother’s ability to actively participate in labor but also experiences physical side effects such as increased nausea, itching, headaches and low blood pressure. Importantly, chemical pain relief can also prolong the duration of labor. Understandably, more and more people are choosing hypnobirthing, a form of hypnotherapy aimed at reducing pain and anxiety during childbirth.

Phobias and anxiety disorders

Treatment for phobias still often consists of forced exposure to the feared stimuli, which can be very traumatic. Fortunately, there are growing offerings of cognitive behavioral therapy, exposure therapy and hypnotherapy, which expose patients to their fears in a safe and gradual way.

Smoking and other addictions

In the past, some addictions were treated with physical restraints and forced abstinence. This sometimes brought dangerous situations. Sudden and forced withdrawal from a substance can cause life-threatening withdrawal symptoms, depending on the addiction. These include extreme anxiety, hallucinations, convulsions, heart problems and with alcohol, life-threatening delirium tremens. Moreover, fewer people were motivated to go through such a tough and dangerous course. Now there is more recognition of the role of psychological and behavioral aspects of addictions. Therefore, when treating addictions, hypnotherapy is a welcome help in overcoming mental dependence.

Hysterectomy

The Greek word “hysteria,” meaning uterus is the basis of the term “hysteria” used in the past to describe a wide range of physical and mental symptoms in women thought to stem from dysfunction of the uterus.

Hysteria was said to be an excessive emotional state with symptoms such as nervousness, insomnia, sensations of suffocation, muscle cramps,anxiety, mood swings, fainting, nervous tics, unexplained physical symptoms, and “uncontrollable” emotions.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, hysterectomy, the surgical removal of the uterus, was performed in some cases as a treatment for “hysteria.” Neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot and numerous others hypnosis doctors used hypnotic techniques to treat hysteria instead. Charcot believed that hysteria was a neurological disorder and that hypnosis could be used to relieve the symptoms.

Lobotomy

Lobotomy is a surgical procedure that cuts connections in the brain, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for complex thinking, decision-making and personality, among other things. The technique was introduced in the 1930s by Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz, who believed that mental disorders were caused by fixed pathways in the brain and that cutting these pathways could alleviate symptoms. The technique was popularized in the United States by physician Walter Freeman, who developed a simpler procedure known as the “transorbital lobotomy” or the “icicle lobotomy.” In it, after a patient is rendered unconscious by electroshock, an ice pick with a hammer is struck through the eye socket seven centimeters deep into the brain and then moved back and forth to break the brain connections. In the late 1950s, the popularity of the method declined rapidly as the serious side effects and ethical problems became apparent, along with the introduction of the first effective antipsychotic drugs. With the emergence of hypnotherapy as an alternative approach in psychiatry, some psychiatrists were inspired to use hypnosis instead of lobotomy. Although hypnosis did not always completely replace lobotomy, it was sometimes used as a less invasive and more targeted approach to influence certain symptoms and behaviors.

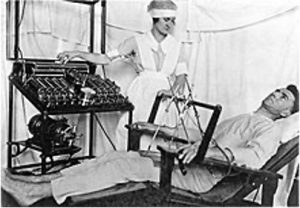

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

In the history of psychiatry, quite a few treatment methods have been used for mental disorders. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was an aggressive treatment method ofpsychic disorders that used electric current to induce a controlled epileptic seizure. There were quite a few drawbacks to this treatment. Among the most common side effects of ECT are memory loss, unconsciousness and muscle contractions. In addition, confusion, disorientation and headaches were common after ECT treatment, and quite a few patients experienced cardiovascular symptoms such as faster heart rate and high blood pressure. Separately, it was a traumatic experience for the patient and was associated with stigma and negative side effects.Despite a mouthpiece, patients sustained permanent damage to their teeth as they bit their teeth hard together during the attack. Although rare, due to muscle spasms, more serious complications such as fractures, dislocations or injuries to joints are also known. In the 1950s, hypnosis was introduced as an alternative less invasive treatment for certain mental disorders.

Pharmacological treatment

Many patients are treated with medication for conditions such as anxiety disorders and pain. Hypnosis is still considered an alternative to medication. For example, in the context of pain management, hypnotherapy is applied to help patients change the perception of pain and reduce pain without reliance on medications.

Parenting and education:

Traditional educational methods often place a strong emphasis on compulsion, with special learning pathways for children with learning disabilities and an abundance of homework and extracurricular activities. This leads to excessive stress and lack of self-confidence in many students. However, there are alternatives that offer a gentler, more effective path to learning. One such approach is hypnotherapy, a technique that has been used for more than a century to treat learning and behavioral problems in children. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, pioneers such as French hypnotherapist Edgar Bérillon used hypnosis to enhance the learning experience. Bérillon and other progressive educators of the time used hypnotic suggestions to improve memory and concentration, promote self-confidence and reduce unwanted behavior. In the Netherlands, A.W. van Renterghem, P. Bierens de Haan and M. Preijes, among others, followed this trail. Although hypnosis has not yet gained wide acceptance in the world of education, it offers potential as a friendly and effective tool for pedagogical approaches. It can help children change their negative beliefs about learning and improve learning strategies. Unlike traditional approaches, hypnotherapy offers more supportive and less stressful help to children with learning disabilities. With it, they learn stress reduction and relaxation techniques so they can better handle their schoolwork. Hypnosis also appears to be a powerful tool to help students increase their self-confidence and improve their learning strategies without medication. Nevertheless, the traditional approach of special education and medication is still the norm. Pharmacological interventions, such as the use of methylphenidate (Ritalin) for ADHD, became increasingly common in the second half of the 20th century.

Behavioral medication.

In modern Western society, there is a worrying trend where more and more children with behavioral problems are prescribed medication. These medications are often designed to suppress aggressive or difficult behavior. While sometimes effective, they often have side effects and can ignore the underlying causes of the problem. The side effects of these drugs can range from physical symptoms, such as insomnia and decreased appetite, to emotional effects, such as apathy or emotional flattening. Moreover, they often provide only temporary relief and can create dependency. Against this background, hypnotherapy offers an alternative that is less risky and more holistic. It works on the root causes of the problem with relaxation and focused attention to bring about changes in behavior and emotion. With hypnotherapy, positive behavioral changes can be promoted without unwanted side effects of medication. © Johan Eland Literature Berillon, E., 1886, De la Suggestion envisagée au point de vue pédagogique Berillon, E., 1898, L’Hypnotisme et l’orthopédie mentale Berillon, E., 1913, L’aphronie et les anomalies du jugement: leur traitement par la methode hypno-Pedagogique Bierens de Haan, P., 1889, Het vraagstuk der beteekenis van hypnose en suggestie voor de opvoeding Bourgery, J.M, s.j., Operazioni della balbuzie [Operations for stuttering] by Jacob, Nicolas Henri; (Florence: D. Serantoni, 1841. Hand-colored lithograph) Esdaile, J., 1850, Mesmerism in India and its practical application in surgery and medicine Roland Holst-van der Schalk, Henriette, 1918, Sunken limits Jong, A. de, 1888, The hypnotism considered as a medicine Mes, L., The prevention of speech defects by educational measures (Utrecht 1927) Metz, Rik, 2016, The problem of stuttering; History of a speech defect in the Netherlands, 1900-1950, Preijes, M., 1899, The question of the significance of hypnosis and suggestion for education, Cure of intellectual and moral defects by the Bérillon method.

Renterghem et al, 1903, Hypnosis and suggestion as aids in the education of children Tudo, Mary, 1939, An experimental study of the effect of evaluative labeling of speech fluency [1] Tongue root m. (-s), posterior and lower part of the tongue.

Anesthesia in dental procedures:

Anesthesia in dental procedures: